Boy Mechanics –

Boys precede men and apprentices precede journeymen. The boy is the father of the man. It is an old saying and a true one. Almost all boys are naturally mechanics. The constructive and imitative faculties are developed, in part, at a very early age. All boys are not capable of being developed into good, practical, working mechanics, but most of them show their bent that way. There are a few cases in which the boy has no competent idea of the production of a fabricated result from inorganic material, but such cases are rare. Given the proper encouragement and the means, and many boys whose mechanical aptness is allowed to run to waste, or is diverted from its natural course, would become good workmen, useful, producing members of the industrial community.

Boys are always planning, contriving, and fabricating. Give a boy a good pocket knife, and, unless the trader is uppermost in his nature, he will use it instead of swapping it, and with its aid he will begin construction, the making of something useful, ornamental or attractive out of handy material. With this comprehensive tool he will do, in his crude way, what the experienced mechanic does with his planes, chisels, gouges, augurs, bits, &c., and be a shipwright, cabinet worker, joiner, carpenter and toymaker in one, and sometimes he will turn out specimens of work that the accomplished mechanic need not blush to own.

There are sold, all over the country miniature chests of wood-working tools ostensibly adapted to the hands of the boy mechanic. But in most cases these are play tools in another sense than that they are of diminutive size. The old notion that “anything is good enough for a boy,” or “any worn-out tool, is good enough for the apprentice” has not lost its force, and these beginners in art and neophytes in work are furnished with miserable apologies for tools that could not keep a place, after a single trial, on the bench of a workman. Such nonsense is reprehensible in theory and wicked in practice. Give your boy and your apprentice good tools and good materials. It is enough for the workman that he can do better work with his years of experience and his ripened judgment, without imposing upon the boy and apprentice with inefficient tools and improper material.

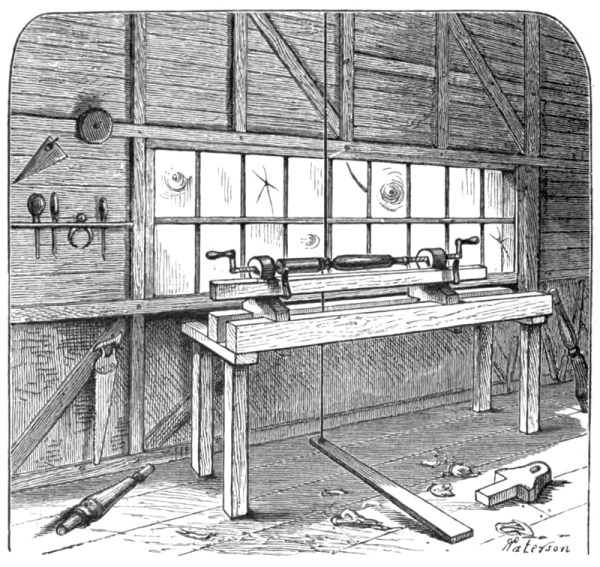

The mechanical boy ought to have a shop of his own. Let it be the attic, or an unused room, or a place in the barn or the woodshed. Give him a place and tools. Let him have a good pocket-knife, gimlets, chisels, gouges, planes, cutting nippers, saws, a foot rule, and material to work. Let the boy have a chance. If he is a mechanic it will come out, and he will do himself credit. If he fails he is to follow some calling that does not demand mechanical skill.

With a foot rule in his pocket the boy will be continually measuring. Before he is aware of it his eye has been educated to judge of dimensions and proportions. It is a good substratum on which to erect the knowledge of practical mechanics. Acquired as an amusement, this knowledge will become practically useful as the boy develops into the man. The employments suggested by the pocket-knife and rule will occupy many an otherwise idle hour, and afford a pleasant relief to the routine of school study and the weariness of oft-played games. The boy will become acquainted practically with substances and be interested in the mechanical operations he witnesses, and this will pave the way for his easy entrance on the vast field of useful endeavor before him. He will become an intelligent and willing apprentice, and a judicious and skillful workman.

Boston Journal of Commerce – c. 1882

– Jeff Burks