How Grindstones are Made –

Berea, Ohio is a town of 3500 inhabitants, situated on the Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati Railroad, and the Cleveland and Toledo Railroad, twelve miles southwest of Cleveland, and six miles from the shore of Lake Erie. It has long been favorably known as the location of the Baldwin University, the German Wallace College, and the extensive and valuable stone quarries.

Either of these interests is sufficient to give the town a position of some importance in Northern Ohio, but its grindstones make it known in business circles as the great emporium of sharpening material. The quarries are situated along the bed and banks of Rocky River, a small stream, and a smaller creek falling into the river about the centre of town. They are now open for three miles on the river, and one mile on the creek.

The quality of the stone was discovered in 1830, by John Baldwin, a name of many eccentricities but some most excellent qualities. In 1830 and 1831, he employed two Irishmen to cut two tons of grindstones in his cellar. These were mostly sent to Canada for a market. In 1832, Mr. Baldwin invented the present method of turning stone, and commenced operations, the whole season’s work amounting to about twenty tons—a sufficient quantity to stock the market. These first efforts produced very indifferent stone, but success finally crowned the effort. The business has increased until it now employs, in all its departments, about a thousand men, and over $1,000,000 capital.

At the present time there are opened eighteen different quarries, employing eighteen engines, besides three lathes run by water-power, with derricks, tram-ways, horses, and blacksmith-shops almost numberless. During the time from seven o’clock in the morning to six at night the quarries present a busy scene, and resound with the music of picks, hammers, sledges, and drills of workmen. It is a busy, bustling scene, but one that tells of money, prosperity, and fortune.

The Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati Railroad has run a branch road from the main line up the river and creek, through the quarries; which, with its extensive switches, makes about five miles of road. The amount of building stone, flagging, spalls, and grindstones carried from the quarries is immense, averaging now forty car loads per day, or 2800 tons per week, making for the thirty weeks of business in the year a total sum of stone shipped from the Berea quarries of 84,000 tons.

These figures are large and almost incredible, but as each car is weighed and registered, we think they must be about correct. The business is so great that it requires two locomotives constantly employed in hauling out and arranging these cars into proper trains on the main line. It is estimated that the whole amount of last year’s make [of grindstones] was upward of 7,000 tons. The stones varied in size from five inches in diameter and one inch thick to six feet by fourteen inches, and in weight from four pounds to 3000 pounds.

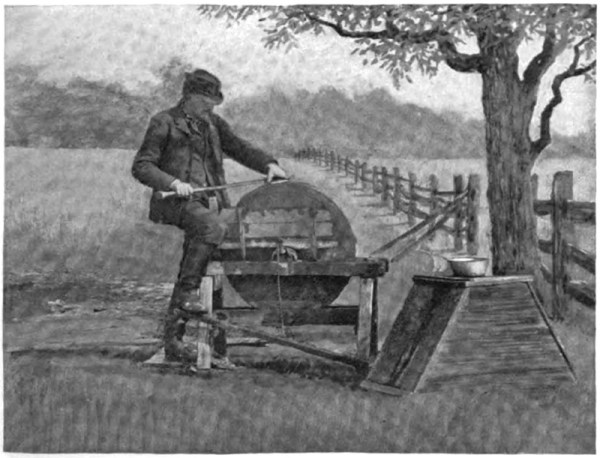

The process of manufacturing is not intricate, but still requires skill to make a perfect grindstone. In the quarry the stone is broken into blocks across the layer, according to the kind of stones required. The block is then turned on it’s edge and, with wedges, is split with the grain of the stone into their patterns as easily and as smooth as one can split a straight-grained stick of pine. The corners of the stone are spalled off, and the pattern is ready of the eye.

Now comes the fulfillment of the old proverb, ‘Sharp enough to see through a grindstone when there is an eye in it.’ The turner takes it, fastens it by rings and keys to the mandrel, and sets it revolving. The instruments for turning are bars of Swedes iron, sharpened at first at the end and afterward hammered down to a broad point. The process of turning is rough and hard, but requires considerable skill to give a symmetrical form to the stone.

The fine grit—an impalpable dust—flying from the stone is productive of a grit consumption. Formerly the average life of a turner was only five years. In late years a fan has been invented, inclosed in a drum, by which this dust is drawn away and carried out of reach of the men, and pure air supplied. Turning is not now considered so unhealthy an occupation, and the average life is lengthened.

Grindstones are shipped to all parts of the United States, and some have been sent to England, to Siberia, and to South America. The casual observer wonders what becomes of so many stones; but his wonder may cease when he remembers the multitude of extensive manufacturing establishments requiring the use of these stones for polishing purposes.

We are told that several plow factories are now using up from twenty to thirty tons per year. The demand in the fast improving West can hardly be supplied. With the opening of every new farm or shop in the wilds of the western world there is created demand for more edge giving material.

Within the past four years workmen have been imported from England and set to work making scythe stones. They are now making six different styles of these useful implements. Besides the common kind of our boyhood days, they make the Darby Creek, English round, English flat, and comminute stones.

The time was when the trade in chips and whetstones was a business of no great respectability, but now the whetstone business of Berea amounts to $10,000 a year. Whetstones possess a real commercial power. Henceforth let not the world despise the whetstone or razor-strop man. They are men of decided sharpening power.

The upturned and disturbed condition of the quarries gives to the town of Berea any thing but an attractive appearance. It is ragged and jagged, torn and rent, and strewn with stones from one end to the other. Where ten years ago good houses were standing, large quarries are now opened, and hundreds of busy hands are digging and picking and pounding, as if for dear life.

The resting place of the dead is not left undisturbed. Already the graves of one cemetery have been removed to give its place to the stone interests, and now the question is being agitated of a second removal. We can no longer inscribe on the monuments of departed loved ones ‘Rest in peace,’ for, if the interests of business and wealth so decide, the dead must give place.

The Cincinnati Gazette – 1869

– Jeff Burks