Uncivil Engineering –

This is an excerpt from “The Anarchist’s Design Book” by Christopher Schwarz.

On the outside, we are all different organisms. Different hair, skin, weight, height, clothes and surface decorations (tattoos, makeup, scars). These differences tell others our age, gender, wealth and place in society.

If you strip us naked and shave us bald, our differences fade. Slice away the flesh and muscle, and you would be hard-pressed to tell your mother from your worst enemy.

It’s the skeleton – the framework upon which all of our personal ornament hangs – that is most like the furniture of necessity.

This might seem an obvious observation, but I think it is a useful tool when looking at or designing furniture. When you can see the skeleton, then you can design furniture that is functional and, with a little more work, beautiful. You just have to start thinking like an orthopedist instead of an oil painter.

The first step is to accept the following statement as fact: Most of the problems in designing and building furniture were solved brilliantly thousands of years ago. The human body is still (Golden Corral excepted) the same, as are our basic spatial needs.

Therefore a real study of furniture should focus first on the things that haven’t changed – table height, chair height, the human body, our personal effects, the raw materials, joinery etc. Intense study of ornament is interesting, but ultimately that will make you an expert in bell-bottom jeans, things that have been Bedazzled™ and feather boas. (See also: props in a Glamour Shots franchise.)

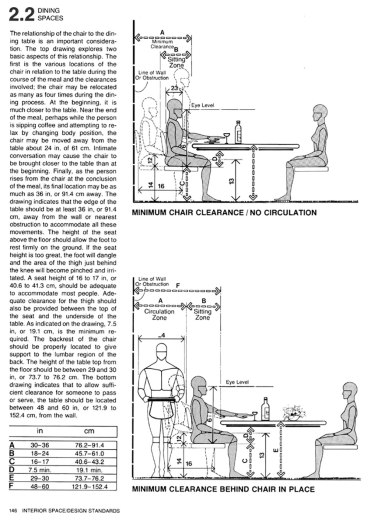

Where should you begin this study? Luckily for us, there is a group of scientists who has done all the work for us: the anthropometry engineers. The bible of this field of science is also my bible of furniture design: “Human Dimension & Interior Space” by Julius Panero and Martin Zalnik (Whitney Library of Design, 1979).

This widely available and inexpensive book (about $6 used) is everything a furniture maker needs to know about the spatial needs of the human body. What are the ranges for chair height among children and adults? Where should you put chair slats to offer proper back support? At what angle?

How big do tables need to be to seat a certain number of people? What are the important dimensions for an office workstation? A closet? A kitchen?

If a dimension isn’t listed in “Human Dimension & Interior Space,” then you probably don’t need it.

Get the book. You don’t have to read it – it’s a reference work that will stay with you the rest of your life. Every designer should have a copy.

Aside from anthropometric texts, early pieces of furniture can tell us a lot about basic furniture design. These pieces were far simpler – I would say “elegantly Spartan” – than what is typical today, even in an Ikea store. But there aren’t many of these early pieces left to study.

We have some beds, stools and thrones from the Egyptians, but we have no way of knowing if these were in widespread use. Egyptian tomb paintings offer additional details, but it’s important to remember that these are mostly depictions of royalty and the things they made their slaves do while dressed in their underwear.

Thanks to a volcanic eruption in 79 A.D., parts of the Romans’ physical culture – both high and low – have survived. And in the Middle Ages we can paint a picture of daily life thanks to paintings and drawings of everyday life. But it’s not until the 1500s that surviving pieces of furniture start to tell their stories.

The stuff that survived is – no surprise – the furniture of the wealthy. It is elaborate, well-made, expensive and put into museums. Academics devote careers to studying it. Collectors hoard it. Furniture makers – both amateur and professional – study it and copy it.

Ordinary stuff was too ordinary to preserve or study, and so it ultimately became useful one last time, as firewood.

Not everyone was happy with the raw deal handed to simple furniture. Many reformers – William Morris and Gustav Stickley, for example – sought to bring good furniture to the masses. Their efforts were noble but doomed because we are natural cheapskates.

— MB